Section 9: Group Dynamics

What you’ll learn to do: Explain and explore the tension between individual versus groups and group dynamics in organizational life.

When it comes to completing work, managing projects and achieving goals, managers have many choices on how they manage the people they lead. They can deal with each of their subordinates individually, assigning individual goals and allowing them to work alone. Conversely, managers can look at their subordinates as one large group, or a subset of smaller groups, and set them on a course of solving organizational problems and achieving objectives.

What are the pros and cons of choosing to assemble a group? And how does it compare to assigning an issue to a single subordinate?

Learning Outcomes

- Describe various types of groups

- Define successful group development

- Determine successful group structure

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of working as a group rather than as an individual

Types of Groups

If you went to high school, then you already know more about groups than you think! Were you one of the cool kids? One of the brainy, studious ones? Did you join the chess club? French club? The football team? All of these, the clubs and cliques you were a part of, and the ones you weren’t, are groups. And they can be classified in a number of ways. Let’s talk about the types of groups one might encounter, in life and especially in the workplace.

A group is defined as two or more individuals, interacting and interdependent, who have come together to achieve a particular objective. Groups are either formal or informal. A formal group is a designated work group, one that is defined by an organization based on its hierarchical structure, with designated tasks related to its function. In the workplace, that might be the finance group or the human resources group.

Practice Question

Formal groups are relatively permanent and usually work under a single supervisor, although the structure of the formal group may vary. For example, the finance group works under the chief financial officer at an organization. There may be groups within the finance group, like the accounts payable group and the treasury group, each with their own supervisor as well.

Task forces and committees are also formal groups, because they’ve been created with formal authority within an organization. Task forces are usually temporary and set up for a particular purpose, while committees can be more permanent in nature, like a planning committee or a finance committee, and can be an integral part of an organization’s operation.

An informal group is one that’s not organizationally determined or influenced and usually formed by the members themselves in response to the need for social contact. For instance, your workplace might have a group of people who get together during the lunch hour to knit and help each other with yarn projects, or a group that is drawn together by cultural similarities and wants to introduce the rest of the organization to their traditions.

An informal group is one that’s not organizationally determined or influenced and usually formed by the members themselves in response to the need for social contact. For instance, your workplace might have a group of people who get together during the lunch hour to knit and help each other with yarn projects, or a group that is drawn together by cultural similarities and wants to introduce the rest of the organization to their traditions.

Informal groups are important in that they exist outside the formal hierarchy of an organization but are the structure of personal and social interactions that managers are wise to respect and understand. Employees motivate one another, informally (and formally) train one another and support one another in times of stress by providing guidance and sharing burdens. In fact, if one employee in an informal group is subject to an action by the organization that the others see as unfair, strikes can happen until that situation is corrected.

Within the group categories of formal and informal, there are sub-classifications:

- Command group. This is a formal group, determined by the organization’s hierarchal chart and composed of the individuals that report to a particular manager. For instance, the manager of training has a command group of his employees, the training group.

- Task group. This is also a type of formal group, and the term is used to describe those groups that have been brought together to complete a task. This does not mean, though, that it’s just a group of people reporting to a single supervisor. The training group, used in the last example, is not the same as the task group that provides onboarding training for a new employee. The training department might provide the outline for how a new employee is brought into the company, but an onboarding task group would include that employee’s manager, an IT manager who equips the new employee with a computer and phone, and so on.

- Interest group. An interest group is usually informal, and is a group of people who band together to attain a specific objective with which each member is concerned. Within an organization, this might be a group of people who come together to demand better working conditions or a better employee evaluation process. Outside of an organization, this term is frequently used in political situations to describe groups that give a point of view a voice. This includes groups like the National Rifle Association, the AFL-CIO and the NAACP.

- Friendship group. These are groups of people who have come together because they share common ideals, common interests or other similarities, like age or ethnic background.

People join groups for a number of reasons. They might be looking for affiliation, a fulfillment of social needs. Groups also add to an individual’s sense of security, status or self-esteem. Or perhaps a goal is easier to accomplish if a group of people concentrate on achieving it, pooling their talents and knowledge. Or, the sheer size of the group might provide the power and influence needed to accomplish the goal.

Practice Question

Groups are an inevitability in the workplace. Understanding how and why they come together is the first step in understanding how they function and how they can function well. However, there are plenty of arguments out there for individual work, and understanding the individual’s need to succeed in the workplace independent of others. Which is right? We’ll discuss that next.

Group Development

The story of every feel-good sports movie—from The Bad News Bears to Hoosiers to Miracle to The Mighty Ducks—is one about a group that came together clumsily and without much hope and went on to win big. As moviegoers, we sit in the darkened theater and root them on as they meet, fight, cry, learn about each other, and finally gain an understanding of how to work well as a single unit. And when we think all hope is lost, and then that last goal/point/home run is scored . . . well, pass the tissues, please.

Now, you may think, “Those aren’t good movies. They’re all the same!” And you’d be right. But it’s not because screenwriters set out to plagiarize a good idea. It’s because the Bad News Bears, the Hoosiers, the USA Hockey players and yes, even the Mighty Ducks, went through all the normal stages of group development, and their group development is the basis for their story.

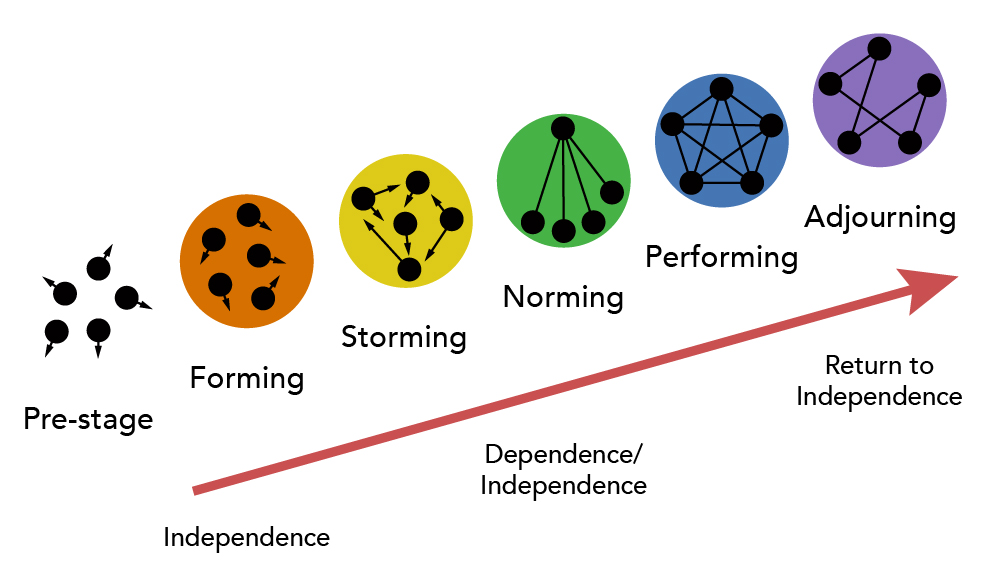

Groups generally proceed through a sequence during their evolution, and that sequence is called the five-stage model.

In the pre-stage, you have a group of people who have never met and probably do not yet know they’re going to be a group.

But the minute they meet, either formally or informally, the members start to go through the forming stage. There’s a whole lot of uncertainty in the forming stage. The members of the group don’t necessarily know the group’s purpose, who their leader is, or what the structure of the group is.

The storming stage is one of intragroup conflict. Members are resistant to the constraints the group imposes on them individually. The group may attempt tasks and fail. There is likely even conflict over who’s the leader of the group.

All of a sudden, close relationships will start to develop between the group members, and a cohesive bond may start to form. A sense of camaraderie and purpose starts to develop. This is the norming stage. During the norming stage, the group will determine a correct set of behaviors that are expected of every group member, and group structure will solidify.

The fourth stage is performing. The structure of the group is fully accepted at this stage, and the group members are getting to know each other well, understanding how to work together to complete the task at hand. They are fully functional.

A permanent group will continue in the performing stage and stop there, but a temporary group, like a task force or a temporary committee, may proceed on to the adjourning stage. In the adjourning stage, the group moves their focus from performing to wrapping up tasks. Members bask in the accomplishments of the group, or become depressed over the loss of camaraderie and friendship they found within the group.

Practice Question

The five-stage model also doesn’t account for organizational context. For instance, a group of three members of a cockpit crew can have never met but still jump immediately to high-level performance, due to the organizational context surrounding the tasks of a cockpit crew. Any group that needs a set of rules and tools, but can forego the time it takes to make plans, allocate resources and determine roles is going to jump a few steps on the model.

The five-stage model also doesn’t seem to work well for temporary groups that face deadlines. These groups have their own set of sequences.

For instance, a committee of senior leaders and key organization members came together at a retail company to plan a large leadership event. The event was to be educational, and would drive home the point that their retail store leaders and their delivery of the customer’s shopping experience was key to future success. Educational breakout sessions would underscore that message. The event team, under that instruction, began working on the agenda and started to contact possible speakers.

At the same time, the company’s marketing department was getting ready to unleash a new brand strategy on the company. Originally set to be introduced in late spring, the event planning group saw an opportunity to unveil it with dramatic style at the leadership event. The senior leaders and key organization members got together again, and, after some discussion, entirely scrapped their original plans and started working on the best way to introduce their new brand to the group.

This is a classic case of punctuated equilibrium. Punctuated equilibrium is a term borrowed from evolutionary science that states that once a species appears in a fossil record, it will be stable and show little change over its evolutionary history. The same is true for these temporary groups, who appear and become stable for the time it takes to complete their tasks.

In Figure 2, you can see that the first meeting of the group sets the group’s direction. They move forward. Then, when half of their time is used up, a transition occurs that initiates major changes. This usually occurs at the same point in the calendar for all temporary groups. They reach the midpoint and, whether a member has been working for six hours or six months on the task, they all experience a kind of crisis around the impending deadline. The calendar heightens the members’ awareness, and they transition.

The transition is usually characterized by an abandoning of prior habits and an adoption of new perspectives. A revised direction is set (If you’ve become interested in the evolutionary version of this, this is where the species appears!).

After the transition, a second phase of “inertia” happens, as the group completes its goal, usually with a sudden burst of energy at the end. Task completed (Species stable). We can all go home.

This is what happened to the event team at the retail organization. They got together with an initial set of plans and then, halfway through the process, abandoned their original plans for plans they’d not even considered the first time around. There was havoc and scrambling but, as the event planner commented soon after, “This seems right now. We were struggling a little bit to make the first plan a reality, but after the meeting last week, we’re really going to move forward with the right message.”

We understand now how a group develops, but to really understand how they work, we need to understand the structure of a group. What—or who—are the parts of the group that come together to storm, norm, and perform? We’ll talk about that next.

Group Structure

Work groups are not like a mob of people, storming through the streets setting couches on fire over a team win. Work groups are organized and have structural elements that help the members understand who is responsible for what tasks, what kind of behaviors are expected of group members, and more. These structural elements include roles, norms, and status. Groups are also influenced by size and the degree of group cohesiveness.

Let’s take a look at how each of those elements creates a structure that helps the members understand the purpose of and function within the group.

Roles

Bill Gates is perhaps best known as the principal founder of Microsoft. He was the CEO, then the chairman, a board member and now, a technical advisor to the current CEO. He’s also husband of Melinda Gates, father of their three children, the head of their foundation and a media influencer. These are all roles that Bill Gates has to manage in his everyday life.

A role is a set of expected behavior patterns attributed to someone occupying a given position in a social unit. Within a role there is

- Role identity: the certain actions and attitudes that are consistent with a particular role.

- Role perception: our own view of how we ourselves are supposed to act in a given situation. We engage in certain types of performance based on how we feel we’re supposed to act.

- Role expectations: how others believe one should act in a given situation

- Role conflict: conflict arises when the duties of one role conflict with the duties of another role.

Bill Gates

Let’s look at this through the lens of a day in the life of Bill Gates. First, let’s look at him in the role of fundraiser. When he’s looking for corporate donations to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, he may visit the CEOs of other successful corporations. He may shake hands, have some lunches, get some commitments for money from these CEOs. That’s role identity. The actions and attitudes that are consistent with a fundraiser.

Bill Gates may choose to wear a suit and tie when he visits these CEOs looking for donations. He may use “corporate speak” that’s familiar to them. He may purchase the lunch. That might be Bill Gates’ role perception. It’s the way he thinks he should behave in the fundraiser role.

Later, he and Melinda may hold a press conference where he announces to the world that they’ve funded textbooks for 250 schools across the nation. Responses include headlines of “Yay, Bill and Melinda!” People talk on Facebook about how Bill and Melinda are really helping communities. They are meeting our role expectations for them.

Finally, Bill and Melissa race out of the press conference, fight traffic to the airport, and try to get home to the violin recital of their oldest child. This is role conflict. The duties of one of Bill’s and Melissa’s roles is in conflict with another—demands arise from both and need to be managed.

Norms

Norms are the acceptable standards of behavior within a group that are shared by the members.

When we learned about motivation, we talked a little about the Hawthorne Studies. To jog your memory, Hawthorne Electric hired researchers to do a study to determine if higher levels of light increased the production of a work group.

A full-scale appreciation of group behavior and its influence on work groups was uncovered by the Hawthorne Studies in the 1930s. What was discovered was that groups established a set of behaviors. Some of these behaviors were spurred on simply because they were being observed. In other situations, the group collectively established a group norm of production—and those individuals that violated the norm by overachieving were ridiculed for not following the established, albeit unspoken, norms.

There are common classes of norms:

- Performance norms: the group will determine what is an acceptable level of effort, product and outcome should exist in the workplace.

- Appearance norms: the group will determine how members should dress, when they should be busily working and when they can take a break, and what kind of loyalty is shown to the leader and company.

- Social arrangement norms: the group regulates interaction between its members.

- Allocation of resources norms: the group or the organization originates the standards by which pay, new equipment, and even difficult tasks are assigned.

If you wish to be accepted by a particular group, you may conform to that group’s norms even before you’ve become a part of it. Conformity is adjusting one’s behavior to align with the norms of a particular group. By watching and observing that group to better understand its expectations, you are using the group as a reference group. A reference group is an important group to which individuals belong or hope to belong and with whose norms individuals are likely to conform.

When people act outside a group’s norms—perhaps a manager makes sexual advances to his assistant, or one co-worker spreads vicious rumors about another—this is referred to as deviant workplace behavior.

Status

The socially defined position or rank given to groups or group members by others is called status. Status seems to be something we cannot escape. No matter what the economic approach, we always seem to have classes of people. Even the smallest of groups will be judged by other small groups, opinions will be made, reputations will be earned, and status will be assigned.

Status characteristics theory suggests that difference in status characteristics create status hierarchies within groups. People who lead the group, control its resources, or make enormous contributions to its success tend to have high status. People who are attractive or talented may also have high status.

High status members are often given more leeway when it comes to the group’s norms, too, and it makes them more at ease about resisting conformity. If you ever watched television’s medical drama House, the very talented, intelligent and curmudgeonly main character is allowed to act unconventionally and often inappropriately, largely because the diagnostic talents he brings to the group are so rare and valued. He is often assertive and outspoken with the other group members. He’s addicted to pain medications, he hates people and lets everyone know it, and yet his behaviors are tolerated. He’s a high status contributor to the group and they need his talents badly, so they overlook his failure to conform to their norms.

In spite of the high status members taking advantage of the norms and dominating group interactions, equity is an important part of status. We talked a bit about how perceived equity is a motivator for people. If status is observed when rewards and resources are distributed among the group members, then usually all is well.

Size

Does the size of a group affect its dynamics? You bet! But how size affects the group depends on where you’re looking.

As a rule, smaller groups are faster than their larger counterparts. But when it comes to decision making, larger groups end up scoring higher marks. So, if there’s a decision to be made, it’s wise to poll a larger group . . . and then give the input to a smaller group so they can act on it.

A side note about size: groups with odd numbers of people tend to operate better than those that have an even number, as it eliminates the issue of a tie when votes are taken. Groups of five or seven tend to be an ideal size, because they’re still nimble like a smaller group, but they make solid decisions like a larger group does.

Practice Question

Cohesiveness

Cohesiveness is the degree to which group members enjoy collaborating with the other members of the group and are motivated to stay in the group.

Cohesiveness is related to a group’s productivity. In fact, the higher the cohesiveness, the more there’s a chance of low productivity, if norms are not established well. If the group established solid, productive performance norms and their cohesiveness is high, then their productivity will ultimately be high. If the group did not establish those performance norms and their cohesiveness is high, then their productivity is doomed to be low. Think about a group of high school friends getting together after school to work on a project. If they have a good set of rules and tasks divided amongst them, they’ll get the project done and enjoy the work. And, without those norms, they will end up eating Hot Pockets and playing video games until it’s time to go home for dinner.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between performance norms and cohesiveness. In the workplace, there are ways to increase cohesiveness within a group. A group leader can:

- shrink the size of the group to encourage its members get to know each other and can interact with each other.

- increase the time the group spends together, and even increase the status of the group by making it seem difficult to gain entry to it.

- help the group come to agreement around its goals.

- reward the entire group when those goals are achieved, rather than the individuals who made the biggest contributions to it.

- stimulate competition with other groups.

- isolate the group physically.

All of these actions can build the all-important cohesiveness that impacts productivity.

Now that we fully understand what a group is and what its dynamics are, shall we go build one to work on a project? Or . . . wait. Are we better off letting one individual person tackle that particular task? We’ll next talk about making the choice between assigning an individual to work on a project, versus assigning a group.

Group vs. Individuals

Are two heads better than one? We’ve talked a lot about groups—how they come together and operate, what elements need to be in place to ensure they’re successful—but we’ve yet to talk about making choices between a group and an individual when it comes to a particular task.

Are two heads better than one? We’ve talked a lot about groups—how they come together and operate, what elements need to be in place to ensure they’re successful—but we’ve yet to talk about making choices between a group and an individual when it comes to a particular task.

Managers are faced with these choices all the time. After reading all this, you may not understand how there can be a better choice than a cohesive, highly productive group to tackle any problem.

Let’s look at some comparisons.

Group vs. Individual Effort

In the late 1920s, Max Ringelmann, a German psychologist, set out to determine if individuals put forth the same level of effort in a group as they did when they were working alone. He set out to examine athletes engaged in a rope tug-o-war, and found that, in a one-on-one match, each player averaged an effort equal to 63 kilograms of force. In a group of three, that force dropped to 53 kilograms, and in a group of eight…only 31 kilograms of force.

This effect is referred to as social loafing, the tendency for individuals to expend less effort when working collectively than when working individually. What causes it? Well, for one, there may be a perception that some group members are not putting out their fair share of effort, and so others are purposely pulling back on their own contribution. Or, it may be attributed to the fact that the entire group shares responsibility for an outcome, so no one person is held accountable for work that is (or is not) done.

It’s worth noting that social loafing isn’t common across all cultures—it actually has a western bias. It’s pretty consistent in individualistic cultures like the US and Canada, but collective societies, like China, do not exhibit as many social loafing tendencies.

If managers want to make sure that individual effort among their group doesn’t drop, they need to provide means by which individual contributions can be measured.

Decision Making

There are pros and cons when it comes to group decision making as well. The benefits of a decision made by a group are:

- It is made with more complete information and knowledge.

- It considers diverse points of view.

- It is a higher quality decision, because a group will almost always outperform an individual.

- It will lead to a wider acceptance of a solution, because the decision is already supported by a group of people.

In group decision making, decision fatigue can arrive over one decision that’s been drawn out and reviewed over and over without coming to a consensus. An individual tends to experience decision fatigue when faced with a lot of decisions—for example, a study of judges showed that they made better decisions earlier in the day, and the quality of their decisions diminished as the day went on.

Groupthink

A company called Despair, Inc. made a series of posters that poked fun at those black-framed motivation posters that companies began hanging in offices. Posters with lions faces touted the qualities of “excellence” and a set of colorful hot air balloons promoted ideas about “diversity.” In this company’s parody of those posters, one of their best sellers showed a bunch of faceless, suited humans throwing their hands into the middle of a huddle. The poster says, “Meetings: None of us is as dumb as all of us.”

No doubt the poster is referring to groupthink. Groupthink is a group decision-making phenomenon that prevents a group from making good decisions. Groupthink occurs when the group is so enamored with the idea of concurrence that the desire for consensus overrides and stifles the proposal and evaluation of realistic alternatives.

NASA’s Challenger

Perhaps the most famous and most studied example of groupthink occurred when NASA launched the space shuttle Challenger in January of 1986. NASA had already once cancelled the launch due to weather, and they were insistent that it go off without a hitch on its newly rescheduled date of January 28, 1986. But the makers of a fuel system O-ring, Thiokol, warned NASA that, based on cold weather predicted, that part might fail and yield disastrous consequences.

NASA’s internal processes and applied pressure kept those people from speaking up, and in an isolated meeting of Thiokol group members, they weighed the possibilities. The company might not be allowed to work with NASA again if they made too much noise. The part might not fail. And so, they agreed to not make any noise, and to support NASA’s decision to launch.

We all know what happened.

Groupthink appears to occur in groups where there is a clear group identity, where members feel there is a positive image of the group that must be protected. That was clearly the case where NASA was concerned—they already had mud on their faces due to the first postponement of the launch, which cost money and a little bit of their reputation. They wanted to be perceived as the elite organization that could do no wrong.

To avoid groupthink, managers can take the following steps:

- Monitor group size, as participants grow more hesitant to participate in larger groups.

- Managers themselves should play an impartial role.

- Encourage a group member to play devil’s advocate and challenge group decisions.

- Focus first on the negatives of the decision before talking about the positives.

A subcategory of groupthink is groupshift. Groupshift is defined as a change in decision risk between the group’s decision and the individual decision that members within the group would make. That is, group members tend to exaggerate their initial positions when presenting them to the rest of the group. Sometimes, the group jumps in and pushes that decision to a conservative shift, but more often, the group tends to move toward the riskier option.

Why does this happen? It’s been argued that, as group members become more familiar with each other, they become more bold and daring. Another theory states that we admire individuals who aren’t afraid of risk, and those individuals who present risky alternatives are often admired by other members. Regardless, managers do well to remember that groups often shift toward riskier tendencies and can do their best to mitigate those results.

Introverts and Extraverts in Groups

It won’t come as much of a surprise to you to hear this: Introverts aren’t always big fans of working in groups.

As you know, introverts operate internally and draw their strength from within. They like being around other people, but interacting with them requires an expenditure of energy. They don’t always feel comfortable or motivated to interact in groups, but they do often focus deeply on their work.

As you know, introverts operate internally and draw their strength from within. They like being around other people, but interacting with them requires an expenditure of energy. They don’t always feel comfortable or motivated to interact in groups, but they do often focus deeply on their work.

Conversely, extraverts love being around other people, they love participating in groups and gain energy by doing so. They’re nearly always motivated and comfortable interacting in a group.

Managers need to draw out the best of both types of members. In her 2015 article for Harvard Business Review, behavioral scientist Francesca Gino stated that it was the type of leader that had the most impact on these group members. Interestingly, extraverted managers could very easily draw responses out of introverts, but had a tendency to shut down extraverts who proposed new visions and ideas. Introverted managers had the advantage, as they carefully considered all responses and suggestions.

Gino’s group performed a study on a set of stores, and found that when extraverted managers were paired with a passive set of employees, they yielded higher sales. When those same extraverted managers were paired with an extraverted set of employees, their sales were lower than expected. But in both tests, introverted managers yielded higher sales.

Of her findings, Gino noted:

These results suggest that introverts can use their strengths to bring out the best in others. Yet introverts’ strengths are often locked up because of the way work is structured. Take meetings. In a culture where the typical meeting resembles a competition for loudest and most talkative, where the workspace is open and desks are practically touching, and where high levels of confidence, charisma, and sociability are the gold standard, introverts often feel they have to adjust who they are to “pass.” But they do so at a price, one that has ramifications for the company as well.

Practice Question

In managing a group, it pays for the manager to consider how meetings are set up and run, and yet few companies show any evidence of doing so. Arriving at a meeting process that encourages introverts to speak up and extraverts to take time for reflection is a win-win for the group and the company.

- Group Dynamics. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Five Stages of Group Formation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Effort/Capacity over Time. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Performance Norms and Cohesiveness. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Untitled. Authored by: Clker-Free-Vector-Images. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/vectors/people-group-crowd-line-silhouette-312122/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- All Hands On Deck. Authored by: Perry Grone. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/lbLgFFlADrY. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Unsplash License

- Untitled. Authored by: Brooke Cagle. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/g1Kr4Ozfoac. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Unsplash License

- Untitled. Authored by: Kimson Doan. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/AZMmUy2qL6A. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Unsplash License