Information Literacy

In This Chapter…

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the challenges associated with our current information environment

- Understand the layout of the following chapters and how they relate to your project

Summary

The challenges of our current information environment often make us feel like there is too much information and it is all equally bad. While perfect, black and white answers rarely exist, it is entirely possible to move toward better information. The skills and habits in these chapters may be different than other advice you have gotten, but they will help you learn enough about your wicked problem that you can contribute to making it better.

Our Information Environment

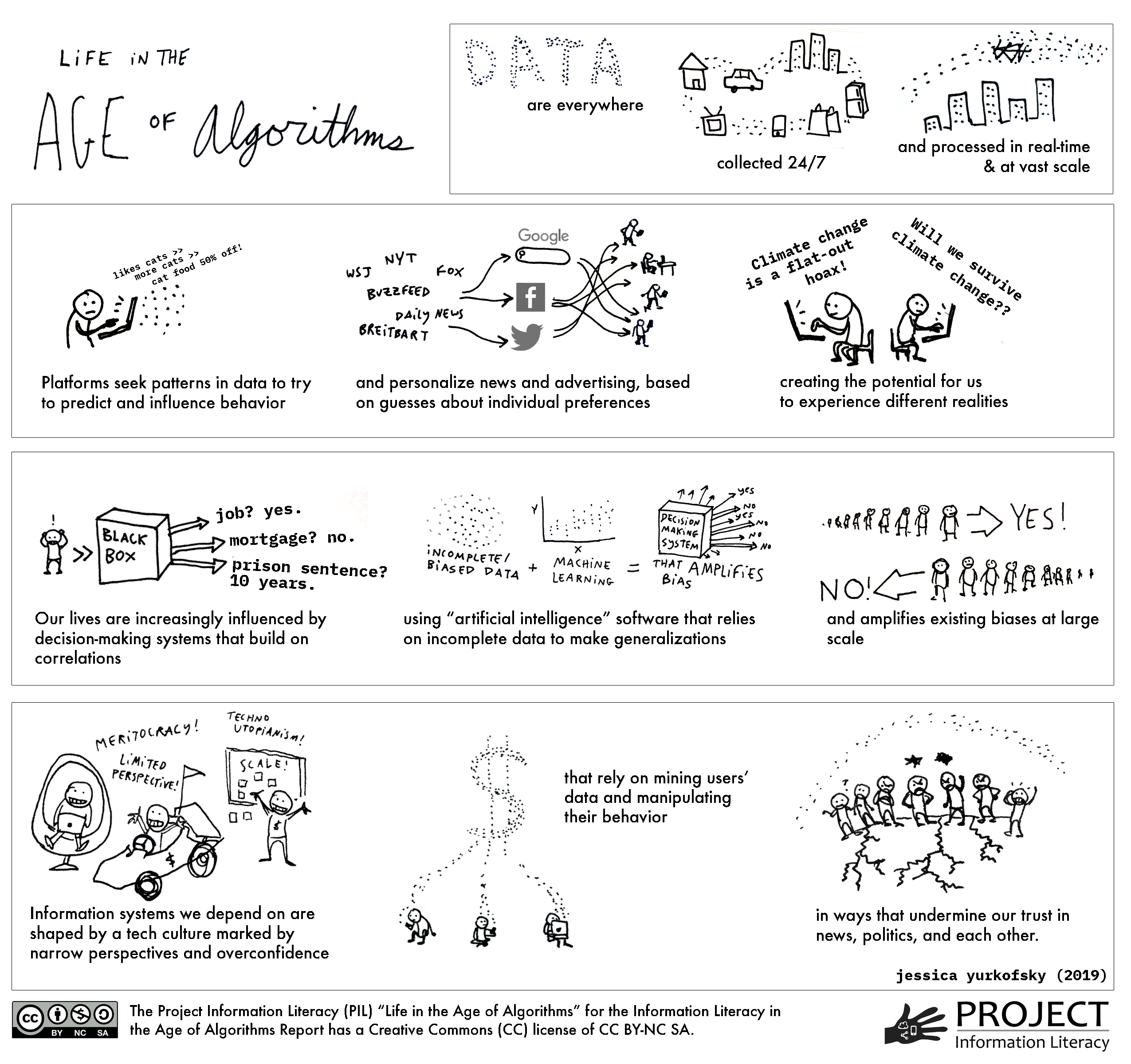

Our information environments are getting more complex, more polarized, and more fragmented. Just a few decades ago, everyone in the United States got their news from the same three networks or the same five newspapers. Today we must navigate, evaluate, and choose among thousands of different content producers and platforms. The proliferation of messages and channels means that it is now possible (and quite common) to choose information sources that closely align with one’s identity, preferences and existing beliefs. This also means that it is possible (and also quite common) to be exposed to a completely different set of information than the person sitting next to you.

Even when we don’t consciously choose sources based on one particular point of view, the platforms we use may choose it for us. Social media feeds and search engines decide what to show us based on algorithms, rule-based procedures for completing a task. The algorithms that determine what each of us sees in our search results and social media feeds are based on the rich, detailed data companies have collected on our past behavior and preferences.

Algorithms aren’t intrinsically bad, but they can have negative and unintended consequences depending on how they are created and applied. A company may only be trying to keep you on their website for as long as possible to increase their advertising revenue. But what happens when they discover that showing you content that evokes a strong emotional response is the best way to do that? What happens when content creators discover that their most polarizing content gets the most views? It’s no wonder our society is so polarized.

With such a large array of sources filled with increasingly polarized content, how are we supposed to get to the truth? How are we supposed to understand our wicked problem well enough to try to make it better?

Information Cynicism[1]

“Without feeling empowered to sort fiction on the web, a lot of students are merely cynical and believe they can’t trust anything” ~Michael Caulfield[2]

This probably isn’t the first time you’ve thought about the problems described above. Within all these competing messages, you may have even begun to feel cynical about the possibility of figuring out the accuracy of anything. If you feel this way, you’re not alone. This feeling is so common right now that it has a name: information cynicism.

- Skeptical: Not easily convinced; having doubts or reservations

- Cynical: Believing that people are motivated purely by self-interest; distrustful of human sincerity or integrity

When it comes to information you encounter in your personal, professional, or academic research, a skeptical approach can be productive. For example, information skeptics might take a moment to fact check, verify, or investigate a source before using or sharing it.

However, when skepticism turns to cynicism, the feeling can stop you from even trying, from taking the steps that are possible to determine the accuracy of information. Information cynics may feel powerless to identify reliable and useful sources. That is, while learning to question everything, they have begun to believe nothing—even highly-credible sources of information.

It is frustrating that our information environment is so difficult to navigate, and it’s ok if you feel this way right now, but let me assure you that this feeling doesn’t have to be the end of your journey. It is possible to make informed decisions about what information to trust. There actually is better and worse information, even if there isn’t always a 100% correct and complete answer. This is one thing we will explore in the coming chapters.

Information Literacy Myths

On this path to better information we may make suggestions that are different from what you’ve been told during your previous research experiences. Here are some of the myths or outdated approaches that we’ll be busting in the next few chapters:

Myth: You should only use library sources/internet sources are bad.

Fact: There are amazing sources available for free on the internet, so let’s use both library and internet sources and not limit ourselves. The internet is an amazing tool for gathering context and moving toward a more accurate understanding of an issue.

•

Myth: Don’t use Wikipedia ever.

Fact: Wikipedia is problematic, but probably not in the way you’ve been taught. Wikipedia is a great tool for preliminary research, although the way it’s created means it is particularly likely to reproduce the biases of its editors.

•

Myth: .org is great/.com is bad.

Fact: There is no gatekeeping of the .org domain, a wide variety of groups can and do use the .org domain. While many reputable organizations use .org, so do a variety of hate groups. The .com domain is short for “commercial” but not everyone who has a .com website has a profit motive.

•

Myth: Some formats are good (books, journal articles) and others are bad (blogs).

Fact: The format of a source is independent of the processes used to create it. A book can be produced by a team of editors, subject experts, fact-checkers, peer reviewers and copy editors, or it can be self-published, with none of these controls. Understanding who created a source, for what reason, and under what kinds of gatekeeping is more useful than limiting yourself to a particular format ever will be.

The Next Few Chapters

Getting a perfect, 100% accurate understanding of your wicked problem would be a difficult, time consuming, and frankly unrealistic goal. Seeking the fullest truth of an issue or situation is the pursuit of a lifetime – you might even think of it as one of the goals of becoming an educated person, one that you will work on your whole life. But on a much smaller time scale, on a day-to-day basis, it is possible to gather the basic facts of a situation, and to make accurate judgements of the information you encounter. Let’s focus then on always improving the quality and accuracy of the set of information in front of us. If we do that, we can get pretty close to the truth. And it doesn’t even have to be painful or extremely time intensive.

After going through these chapters you will be well equipped to do the kind of research that is required to get to know a wicked problem. We’ll go through the process of examining what you already know and believe about your wicked problem and navigating a rich information environment. Knowing how to start research on a topic that is totally new to you will come in handy throughout your college career and, assuming we don’t solve all the world’s wicked problems this semester, your life.

So what level of research do you need to do to participate in the conversation about your wicked problem? How can we find out what the different perspectives are? How will we know we aren’t missing important parts? What kinds of sources are out there and how will we know if the one we found is useful? What will our own participation in the conversation look like? In the next seven chapters we will tackle these questions.

- Our Mental Shortcuts: Our brains have developed some shortcuts to deal with the overwhelming amount of information around us. Usually that’s a good thing, but some of these shortcuts, such as confirmation bias, can have serious consequences for our research. We’ll think about ways we can recognize and mitigate these shortcuts.

- Identifying a Topic: Learning about your wicked problem and identifying an area of it to work on are not separate activities We’ll talk about strategies for reading and learning about your topic that will help you get the big picture and help you find an area of inquiry that is meaningful for you.

- Types of Sources: Before we start searching it’s good to know what types of sources we might find out there. Problem is, there are a lot of different ways to categorize sources. We’ll talk about some useful ways to think about the sources you find.

- Access & Searching: We may start our searches with Google, but there are good reasons not to stop there. We’ll talk about the limitations of different search tools and some strategies for getting the most out of them.

- SIFTing Information: Here we get into some concrete steps that we can use to assess the credibility of a source or claim.

- Evaluating News Sources: It does no good to ignore all news sources that have bias – all sources are biased in some way. When considering the accuracy of news sources it’s helpful to understand the difference between bias and agenda and between news gathering and news analysis.

- Audience, Presentation & Citation: Once you’re informed on your wicked problem and want to share your own perspective, project, or plan, you’ll need to think about the best way to do that. Thinking about your audience will help inform your own creation processes, presentation choices, and even how you choose to cite information.

Reflection & Discussion Question 1: Information Cynicism

Review the description above of information cynicism.

- How accurately does this describe your feelings or those of your peers?

- How do you feel about your ability to navigate your information environment right now?

Reflection & Discussion Question 2: Reflecting on Your Research Education

Think about the research advice you’ve gotten in the past. This could be from teachers, librarians, or friends and family.

- What was the most helpful research advice you’ve gotten?

- Describe a piece of unhelpful advice that you were given, or a piece of advice that didn’t line up with your own experiences of research. What would have been better advice?

Reflection & Discussion Question 3: Looking Ahead

Review the descriptions of the next few chapters.

- What topics are you most interested in?

- What part of research worries you the most?

- What is one research skill you hope to improve?

- What three words best describe how you feel about doing research right now?

Reflection & Discussion Question 4: Looking Back

At the end of the semester, review your answers from the exercises above.

- Were you able to improve on the skill you chose in exercise 3?

- What three words best describe how you feel about doing research at this point? Have they changed?

- What advice or content from these chapters was the most helpful? Least helpful?

- Are there topics or skills that you wish had been discussed that weren’t?

- Content in this section is derived from the Information Cynicism chapter (3.3) of Introduction to College Research (CC BY) by Walter Butler, Aloha Sargent, & Kelsey Smith (https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Research_and_Information_Literacy/Book%3A_Introduction_to_College_Research_(Butler_Sargent_and_Smith)) ↵

- Michael Caulfield quoted in Jeffrey Young's "Can a New Approach to Information Literacy Reduce Digital Polarization?" (https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-03-22-can-a-new-approach-to-information-literacy-reduce-digital-polarization); emphasis added ↵