Main Body

Solving Problems Through Careful Consideration of Philosophical Dialogue

Understanding the Terminology

This chapter will cover terminology and the two approaches related to moral problem-solving:

- Objectivism, and

- Subjectivism.

Objectivism is the belief there is knowledge, truth, or concepts that we strive to make sense of, and they guide us in our knowledge attainment. In ethical terminology, objectivism is best equated with the term absolutism. Absolutism refers to the belief in a universal truth or universal concept of “right” and “wrong,” which exist regardless of individual perception representing reality and knowledge.

Apart from this stance exemplified in objectivism and absolutism, there is the philosophical realm of subjectivism. This terminology refers to the belief that truth, reality, and morality are understood through individual experiences or perceptions. Thus, subjectivism argues that our knowledge of anything depends on our understanding or interpretation. The moral terminology best associated with this belief is the concept of relativism. Relativism is the belief that morality only expresses a personal preference or individual interpretation. Thus, rules of conduct or moral expectations are only a product of personal expression or perhaps even just opinion. This argument is maybe the most complicated and important dilemma found in thinking and problem-solving and has been analyzed for centuries in all cultures. How one interprets the world, their place in it, and their conceptions of “good” and “bad” will heavily impact how they interpret problems and solve dilemmas daily.

Other classifications one might encounter

The objective and subjective stances one may take on any issue relating to problem-solving can be divided into these seven categories, according to thinking experts.

- The first one is the definist religious authoritarianist thinker. This thinker approaches decision-making from the standpoint of arguing objective moral assessment emerges from some supernatural power or authority that has created the conceptions of preferred human behavior. Thus, moral decisions are equivalent to the supernatural power’s commands or expectations.

- The second thinker is the nondefinist religious authoritarianist who argues that moral decision-making is rooted in a supernatural power’s commands of what can best be assumed to be “right” and “wrong”. But, unlike the definist religious authoritarianist, the nondefinist religious authoritarianist denies that the meaning of moral judgments is defined strictly in terms of supernatural command. Though both thinking processes appeal to objectivism, they differ in the extent of that objectivism’s direct connection to such a supernatural power through moral reasoning.

- The non-naturalist thinker believes morality or decision-making is contingent on the truth outside the natural realm. Thus, values or virtues do not exist in our natural world but in the non-physical or supernatural realm.

- The naturalistic objectivist maintains that truth is objective and found in the natural realm. This belief might appeal to natural order or natural law.

- While the naturalist objectivist argues natural processes or natural law dictates what is “right” or “wrong”, the nondefinist naturalist objectivist believes there is no correlation between natural processes and moral thinking despite possible connections. The last two categories focus on the role of the individual or subjectivism in determining morality or “good” decision-making.

- Personal subjectivism argues that whatever one’s conscience decides is the right decision.

- Egoism argues that moral thought is wholly based on individual preferences and that individuals are not obligated to consider the “good” or “betterment” of others.

A Profile of Subjectivism

Thinking and decision-making factors inherent in our world are not far removed from those of the Ancient Greeks. They recorded their problems and discussions, and their writings were passed down. Today, we can read and learn from them. The two best examples of this subjectivism and objectivism interaction can be found in the arguments of the Sophists and Socrates.

The subjectivist thinkers were known during their time as the “wise ones” when many philosophers were involved in both academic and observational studies of the world. They studied everything from cosmology to language and the conceptualization of human thought. A literal academy emerged in Abdera in modern-day Greece, where wealthy sons were educated in, what this group believed, was the truth or the concept of true wisdom. Wisdom was found in the belief in individualistic thinking or “extreme skepticism.”

Extreme skepticism focused on the following questions:

- Are there real ethical principles, or is morality merely a set of arbitrary conventions?

- Are the laws of the state comparable to the laws of nature or mere arbitrary rules?

- Are the genuine moral laws and norms for evaluating human behavior comparable to the laws which govern physical nature?

In response to these questions, they formulated a philosophical, moral, and decision-making system based on relativism and subjectivism. They argued moral principles or concepts of “right” and “wrong” were relative since knowledge is relative. The art of debate or argument was the only thing worth studying regarding leadership. When one’s relative opinion meets one’s other opinion, the winner would be determined by the most talented individual debating their viewpoint.

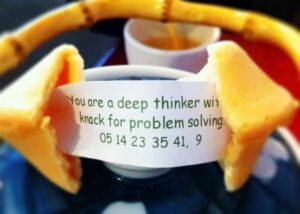

Protagoras c490-420 BC

This perspective is summarized by Protagoras of Abdera, a teacher in the academy from 481-411 BC. He said, “Man is the measure of all things, of things that are, that they are, and of things that are not, that they are not”, or the relativity of truth should determine decision-making, the relativity of morals, and the concept of equality for all, as no opinions were better than others in quality or content. The equality feature led the early Greeks to argue that the best form of government was a pure democracy where decisions could be best determined in the context of voting and majority rule. Therefore, the Sophist viewpoint of Ancient Greece argued that one’s perception was truth and that morality or decisions of “good” or “bad” and/or “right’ or “wrong”, were not useful unless understood in the context of the determination of social norms or codes. This presents an exciting propensity that we all have to believe that our reality is the preferred perspective to accept. Listen to Julia Galef’s discussion on why we think we are right even when we are wrong.

A Profile of Objectivism

Plato argued that objective Truth could be found by pursuing greater knowledge and education. Plato wrote during an age in Mediterranean history where the ideas of Sophism had significantly impacted the societal norms and morals of many Greek city-states.

The contrary argument to the Sophist approach was espoused by the Greek philosopher Socrates. He argued that decisions in life must be directly tied to the pursuit of what can best be termed “Goodness” or the concept of the “Good”. This could be pursued through the constant process of questioning that led us to seek out Truth and gather evidence, not to give up due to our subjective processing. He asserted there is universal or objective Truth apart from human perception or perspectives that help guide our decisions. The more we reasoned and grew in our self-knowledge and the world around us, the more this reality would be revealed. Patterns of life are predictable and reflect a system in which our thinking and reality could best be understood in terms of forms of hierarchy that coincides with betterment or progress.

Though there are elements of relativity in how we gain knowledge of what is “Good” and in the deviation in how humans reach “Good”, Socrates’ philosophy is clear that all types of decisions should be understood in the context of a universal conception of “Goodness”–not merely individual desires or individual perceptions. In short, we must consider the greater “Good” because there is more to this life than our existence or reality.

At the root of these arguments is Plato’s belief that there are “Ideals” we inherently know that help guide humans to assess making value judgments. These ideals are represented by characteristics of preferred human behavior that are not subjective but objective. In this thinking, we find strong evidence for comparison in a monistic framework, where knowledge of “good” and “bad” are found in comparing imperfection with perfection.

Platonic thought asserts that we have concepts of “Goodness” implanted in the realm of ideas. Still, we must find those conceptions through our diligence in pursuing them through a life of moderation, awareness of the world’s ways, and reason. The world provides clues to find that knowledge, but we must also acknowledge that the world is imperfect.

Goodness is found in harmony, virtue, and rationality but not always most easily and conveniently. From our knowledge, we discover values and virtues are passed down from generation. These values and virtues are not relative or merely based on individual assessment but are part of the hierarchy of “Good” that is part of our humanity.

What about happiness?

When contemplating the objective and subjective nature of the world and moral determination, the question arises if there is a correlation between living morally and happiness.

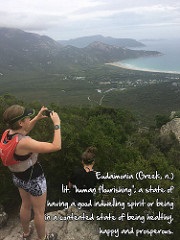

Contrary to Plato and the Sophists, Aristotle believed that true morality and/or ethical living were not found in intellectual contemplation/pursuance of the right pleasures or the one virtue of appropriate care of others. Aristotle was convinced actual ethical behavior was to be found in the rightful knowledge of individual happiness found in “living well”. This conception, though universal in that all factors of living well are the same, is the difference in how we pursue living well. Living well is highly personalized and based upon one’s willingness to search in great depth through practical knowledge and our daily understanding of true happiness or “eudaimonia”. Using Aristotle’s analysis, we should pursue virtuous behavior or characteristics such as honesty and trustworthiness because such values are derived from our rational souls. This instrument promotes constructive reason and goodness for ourselves and others. In the 4th century BC, Aristotle was convinced that people were misled into believing that true happiness was based on one’s conception of material goods or power. Though these concepts are not inherently problematic, the obsession humans often display towards these items leads the world and themselves to be unbalanced, as best understood in his description of the “doctrine of the mean”. In this concept, Aristotle writes that authentic, ethical leadership and moral decision-making are based on understanding the factual balance of extremes, where one extreme’s adverse effects or destructive nature is minimized. How do we do that effectively in a world that pushes us to focus on the result of profit and physical rewards?

Aristotle’s solution, the concept of living a virtuous life, provides three practical suggestions.

- People must set reasonable individual and focused goals based on the belief that a balanced, healthy life emphasizes living well, a concept found in reason and its practical application.

- One will make better ethical decisions when one understands that living well is not based on the accumulation of wealth, material goods, or power; instead, it is based on the habitual practice of virtuous or reasonable conduct where the individual is validated and others, because of these practices, reciprocate.

- The concept of balance or “mean” emphasizes the idea that although the result of ethical behavior is true happiness, true happiness can only be found in the genuine exploration of one’s very being so that one can honestly know what one was put on this earth to accomplish; namely, one’s true mission or the fulfillment of what one’s purpose is.

Dan Gilbert discusses why we make bad decisions (33 minutes). Pay attention to where Gilbert agrees with Aristotle’s assessment.

When one finds true meaning through adherence to reason, proper virtue, the pursuit of goodness, and balance, individuals, groups, and society will benefit, and honesty and trustworthiness will return. Aristotle’s idea of moral excellence argues that authentic leadership comes from allowing individuals to pursue their passions in a genuinely virtuous manner, where material goods are secondary to lives devoted to characteristics of human behavior that bring true happiness and goodness. Those factors can only be found by constant and habitual practices which emphasize moral living. If we want true, long-term happiness, we must be willing to focus on changing these habits by pushing ourselves and others to “live well” in a long-term framework rather than in an artificial short-term framework that often ends in unhappiness, unethical behaviors, and immoral stances.

Listen to Chris Gardners’s 2009 speech. Chris inspired the famous movie The Pursuit of Happyness, 2006. In the speech, look for the correlation between Aristotle’s conception of happiness as it relates to morality and Gardner’s view.

What about Pleasure and Pain?

Beyond the evaluation of happiness and morality, we must also consider the role of the influences of pain and pleasure in determining our moral evaluation within the context of objective and subjective thought. One crucial theory to study is Epicurean thought.

Epicurean thought is often known for its close connection to hedonism. Hedonism is the philosophical perspective that life should be centered around creating the most happiness for oneself. Usually, this is interpreted as happiness grounded in physical pleasures. The perspective of hedonism emphasizes that one should make decisions for the short term with immediate gratification because our time in this world is, at best, fleeting. This “supposed” connection between hedonism and Epicurean thought has been grossly overextended.

Contrary to English definitions and the assumed meaning of the term Epicurean, the philosophical position of Epicurus is not hedonism-based. The core belief runs counter to this. In Epicurus’ (4th century BC) lifetime, many wealthy Greeks believed their culture and social morals were in decline. Epicurus traveled the then-Mediterranean Greek world, and after years of observing this decline, he concluded many Greeks did not have their priorities in the correct order. He returned to Athens in 306 BC, encouraging those around him to withdraw from public service and look inward to find contentment and happiness, not through others’ or society’s expectations.

Where Epicurus is most misunderstood in his explanation of pain and pleasure, he believed the interaction of two powerful forces determined life’s decisions. In terms of an outcome, what we choose directly connects to our understanding of the potential “fallout” of our decisions as determined by the pain vs. pleasure equation. Epicurus argued that we should seek “peace of mind.” The “peace of mind” principle stresses that we should evaluate whether our decision or decisions would create more pain or pleasure for ourselves and others. In addition, those decisions must be contingent on long-term intellectual investments, which he considered the most beneficial. Contrary to popular thought, Epicurus did not simply advocate a hedonistic perspective of living.

At the core of good decision-making is whether to live a life avoiding pain or seeking pleasure. Epicurus delineated the difference by writing; a life lived simply by “avoiding pain” was a de-active form of life with little return on one’s “pleasure investment”. Therefore, one ended up living a life that didn’t maximize their potential for pleasure. The alternative approach he defined as a life spent actively seeking pleasure or the “right” pleasures. He argued that This life was the most satisfying and moral, as decisions based on that perspective would offer everyone involved a greater happiness factor or level of contentment.

This idea of contentment was based on long-term investment in the arena of the mind. Rather than focusing on the result of a life pursuing trivial and materialistic pleasures, Epicurus believed the morality of decisions about intellectual pursuits transcended the limitations of the short-term. Epicurus relies upon the belief that happiness is not directly tied to ecstatic or high forms of pleasure or the attainment of all desires. Both factors are impossibilities, and therefore their pursuit is foolhardy. Instead, many thinkers, like Epicurus, came to determine in their life and by observing others that true happiness is found in the balance and contentment one seeks, finds, and carries out daily.

As a result, Epicurus’ argument, ironically, emphasizes gaining control of one’s decisions while keeping one’s thoughts and emotions in check. He believed individuals who were well-schooled in thinking strategies and good decision-making clearly understood the result of their thinking processes and could see the truth—that true happiness was found in careful and deliberative good moral evaluation, essential for those who were mindful. In following this “self-control” aspect of his theory, Epicurus was convinced that one gained “true freedom” or the ability to escape from the troubles of mind and body. Through intellectual pleasure, in particular, one could find the most significant reward through learning to practice self-control and adequately weighing one’s interests with others. Thus, morality is not found in mere societal norms; instead, each individual must shoulder the responsibility when seeking “true” pleasure, focusing on long-term goals that enhance happiness through balance and harmony with others. Thus, honesty and trust are built not on selfishly getting what one wants but in the development of pleasure through self-control, intellectual understanding, and prioritizing the world of non-material over the world of the material. Epicurus warns us to be careful with the obsession for instant profit or material gain at the cost of other more important elements like the values of honesty, teamwork, self-confidence, reliability, and our legacy.

Outcomes of Objectivity and Subjectivity

It is essential to consider recurring themes through each theory so far when considering the nature of objective and subjective thinking. In studying these theories, three suggestions come to mind.

First, true ethical behavior begins with ourselves, not others. Each of the three theories discusses the importance of weighing individual or subjective analysis either through an intellectual reevaluation of individual behavior/thinking or the setting of one’s priorities with the acknowledgment that we must actively seek true objectivity or an objective process. Our attitude and individual demeanor/behavior significantly impact those around us; perhaps more than possible, rules or regulations are set up or enacted.

Second, it is vital to reevaluate “true happiness.” In the last two theories, each philosopher or thinker attempted a fundamental and new understanding of this concept, whether they found happiness in refined intellectual pleasure or balance/living well. Socrates, Aristotle, and Epicurus struggled with this reevaluation conception and did not merely accept the status quo or the general beliefs of others. All three believed that, left to their own devices, most individuals will not seek proper ethical understanding or act upon it. Instead, individuals are misled by factors and influences that persuade them to pursue false ends and not to think about the ramifications of their attitudes and/or decisions. Thus, it is left to insightful and critical solid thinkers to attempt to lead individuals to think through ethical issues and to support and encourage people to understand true ethical decision-making and, therefore, true goodness, happiness, or pleasure.

Third, all three theories emphasize the importance of acknowledging the focus on true moral thinking in any situation, focusing on goals that tend to be long-term with a focus on good communication and interaction. The conversation about how to best determine and preserve essential components of society that lead to happy and moral societies has long been discussed.

Making Sense of the Objective and Subjective Conversation

The examples from the Ancient Greek world can be assessed today. Both objective and subjective thinking have their place. Subjectivism or relativism can be interpreted to be the more productive and truthful interpretation of “good” decision-making, but this might be deceiving.

There are many attributes to consider that are favorable, though.

- Different cultural societies seem to have different moral norms.

- Each culture has morals that seem acceptable to them.

- It is hard to determine an objective standard for all as that is difficult to assess with one hundred percent assuredness.

- It may be the case that one moral code can not be determined as better than any other, and it is arrogant of individual cultures or societies to believe that they have a better insight into these matters than another.

- Over time, morals seem to change.

First, what was acceptable behavior or thinking years ago often fluctuates or changes dramatically. On the other hand, there are also positive arguments for objectivism or absolutism. Objectivism dictates that there must be a specific set of conduct or rules, and many subjectivists argue is impossible to find or know a code of conduct or rules. On the objectivists’ side, one could argue that there is a peculiar trend when one “boils” down conceptions or understanding of societies and their norms that argues that people do conceptualize similar values or virtues and prize them.

The second argument with a strong objective standpoint is the assertion that individuals seem to have innate knowledge that guides us with “natural” and similar reactions or thinking patterns that dictate similar behavioral patterns. A good example is the statement of relativity, which many argue is a universal standard.

The third argument for objectivism states that our language and conceptualization structure reflects a universal process. Terms such as “good,” “right,” or “wrong” imply universal conceptions of understanding, not relative constructs. The fourth argument for objectivity lies in relativism’s assumption that different standpoints are equal in value. Though customs differ between societies and people, that does not make peoples’ conceptions accurate because they believe them. The weakness of human reasoning often lies in the misperceptions of individuals. It might be possible to assert Truth in decision-making and find objectivity through reason and knowledge accumulation.

The last argument is the most difficult and relies on knowledge attainment. Our knowledge is based on the assumption that information, like in science and math, is truth. We can prove what we believe to be true through the methodology of doubt or scientific method with the inference to the best possible outcome. Truth, therefore, is verified through many reasoning procedures. These procedures have proven Truth in metaphysics, epistemology, science, math, and the natural world; the following logical assumption applies to judgment calls or proper decision-making. Thus, a hierarchy of thinking and values must exist, and a “better” way of living and making decisions must also exist. Both arguments about this important evaluation principle have value and worth. Thinkers must consider the implications of one’s assumptions about morality and values.

The Issue of Free Will vs. Determinism

Another component we must consider when evaluating objective and subjective thinking is the influence of free will and determinism theories. By definition, free will is the argument that we can make choices that influence ourselves and others. Determinism, the contrary argument, espouses we cannot make choices that influence ourselves and the world around us. Though these definitions are much more complicated in the philosophical study, looking at these two approaches to life and the hybrids in peoples’ thinking is vital.

Whether we know it or not, our view of the world and our place in it are heavily impacted by our control or perceived control over ourselves and reality. Almost everyone has contemplated their level of control to change their circumstances or dictate their future. At the heart of this question is the thought process which is an important thinking dilemma: free will vs. determinism. In a philosophical sense, free will can further be defined as having all choices available at any point in time, while determinism, in its purist philosophical conception, centers on the conception that individuals have no control over factors that dictate a change or the future. The implications of such viewpoints are considerable for business, psychology, law, and even personal relationships.

Let’s look at the various “hybrids” that exist and then build on those concepts to understand better how such factors impact this interplay of objective and subjective thinking. The critical thing to remember about the interplay between these beliefs is that intention and action are essential factors to trace and think through.

- The first approach to this thinking dilemma is libertarianism. Libertarianism states that individuals choose freely daily and must assume responsibility for those actions.

- Hard determinism argues that there are no free choices. In the time and space we make decisions, other factors like cause and effect and environmental factors (factors outside ourselves) have dictated that it is impossible to argue that we have the freedom to choose anything.

- Soft determinism espouses the argument of compromise, advocating that cause and effect factors play a part in our choices; thus, determinism does make sense, adhering to arguments stating that we have some freedom to make decisions within a limited framework. The work of Harry Frankfurt best supports this theory in his text Free Will. He argues that soft determinism, or the workings of free will, coincides with layers of desire. The first layer he refers to is first-order desires or desires we have no control over. Though connected to first-order desires, second-order desires demonstrate the free will, as he explains that we have control over the reaction or influence of the first-order layer of desires. Frankfurt’s theory demonstrates the incorporation of both free will and determinism.

- The free-will-either-way theory claims that free will exists but that it is essential to understand that its existence is tied directly to the fundamental control of determinism. In short, free will directly connects with determinism, which works together to create reality.

- Finally, the counter to this, referred to as the no-free-will-either-way theory, states the exact opposite. No free will exists as it is directly connected to deterministic factors. Thus, though both conceptions exist, determinism overrides the freedom of “free will” by naturalistic influence. All five approaches are incredibly important to consider when evaluating essential decisions.

Cause and Effect

It is easy to fall into a framework acknowledging that we have little or no power to change factors that influence us or our society. Problems emerge from daily decisions that impact every one of us. In our society, many people argue that they can do very little to change these dilemmas. This belief permeates society and, in reality, is only somewhat true. We are a product of factors such as our background, environment, education, thinking, and beliefs. The issue is whether we have the means to work beyond such factors if they lead us to make decisions that continue potentially destructive habits. Will we follow the path that has been directed for us?

The answer to this question is complicated, but there must be some acknowledgment that free will must be tempered with determinism and not left to forms of fatalism. Choices matter whether other factors determine them or not. We are left with assessing, to the best of our ability, the concepts and knowledge given to us, with the understanding that whether we conceive of determinism or free will, we still must progress into the future. The best way to conceptualize this is in leadership terms. If a company has instituted policies that have caused those in power to assess decisions made at that point about those past decisions, then regardless of whether those decisions have been productive, the determinism of the past decisions has dictated the factors that have produced the current dilemma. Watch Sheena Iyengar discuss the implication of the art of choosing.

Ivengar says possessing choices and freedom is a noble goal, but she also presents the importance of realizing how our life factors influence our decision-making. The free will element in that determinism allows for decision-making that aligns with that series of decisions or reverses against past policies. Awareness, knowledge building, and careful consideration of all factors can help to determine; in a greater capacity, the root one should take in a particular moment. Adhering to a more subjective standpoint supports the argument that past events or other factors should not impact moral responsibility and decision-making. Thus, what makes sense is a perspective that takes responsibility for past decisions where appropriate and attempts to move forward with a strong desire to improve the situation. This is where ethical study can help.

Thinking Well

Looking at the many factors that determine our moral thinking encourages us to be more self-aware of the thinking of those around us and the conditions in our society that have shaped our world. Considering the value of thinking about objective and subjective thinking, contemplate this question: how can thinkers better navigate the world by being aware of the interaction of objective and subjective thinking and its by-products?

Many people conceive of the world around them as distant from their reality. Therefore the implications of their actions or thoughts are unimportant to them, outside of the impact these decisions might have on them directly. This view, as stated earlier, called egoism (or what the Ancient Greeks termed Sophism), can be a frightening approach to citizenship, decision-making, and good thinking. Thinkers must be committed to weighing where relativistic thinking, the acknowledgment that decisions and thinking must be understood as relative to the situation and the context. Relativistic thinking must be used constructively while also coming to a clear ideology or understanding of what factors are absolutistic; in that assessment, they must seek out Truth amid such a complicated and troubling dilemma. Absolutism or objectivistic thinking can aid thinkers by reminding them to think through the limits of relative thinking or context by seeking out commonalities in principles, values, virtues, and a conception of the future that will be built on an ideology or series of ideas that are well-thought out and follow good moral evaluation.

Three suggestions from various texts and theories come to mind. The first conceptualization comes from the author Paul Loeb who wrote a book entitled Soul of a Citizen in 2000. In that book, Loeb suggests that the key to solving the crisis of our citizenry is to build a society in which thinkers begin to help solve societal problems by determining with greater clarity what factors of change or relativity are essential and what factors should be held unto. Perhaps the most significant factor he thinks we need to start with is honesty.

The second suggestion comes from the work of John Finnis, professor of philosophy at Oxford University, who argues the key to understanding objectivity and relativity has to do with seven factors which he claims confirm the validity of objective thought and force us to work towards a world of greater connection, responsibility and sympathy towards those around us. He writes that life, knowledge, play, aesthetic experience, sociability, practical reasonableness, and religion confirm the importance of our connections and demand we work towards a world in which we acknowledge our unique contributions to it but also realize humanity’s undeniable objective tie.

The last theory, espoused by RH Hare, professor of philosophy at the University of Florida, argues the object of moral thinking in subjective and objective terms must ponder the universal idea of the “right” way to act. That concept of the “right” way suggests a common conception, through reason, of the values we hold to as a community, country, and worldwide community. Thus, discussing objectivity and subjectivity becomes the most critical thinking dilemma for individuals to consider about societal and personal “betterment”, regardless of industry, profession, time, or location.

What Can We Learn in the End?

How do we become more aware of the interplay of subjectivity and objectivity to create institutions, communities, society, and the world that reflect good constructive thinking and decision-making? Every theory takes a stance on reality, social justice, or morality and believes that objectivity is the more significant factor in determining Truth or the right way to solve a specific problem. The premise of their observations and statements infers change. This change adheres to values and expectations of behavior and appeals to such concepts as justice, fairness, and appropriate treatment of all in our society or world. Though many may disagree on how to solve such problems, the thinking at the root of such conceptions favors a more objective stance with relativistic factors to consider.

This is true even when we employ the best thinking tool possible–the practice of inference to the best explanation. This principle argues that we must use what makes sense by thinking of the possible outcomes while evaluating good reason and building consensus. Thus, we must be prepared to infer through what we think we know the best possible outcome.

Another element to consider about this critical question is GE Moore’s theory of organic unity. GE Moore was a prominent thinker in the early twentieth century who taught at Cambridge University. He argued that in simplicity, the moral acts we choose should not be limited to pleasure seeking or egoism but must consist of what we believe to be proper conduct based on the most productive outcome. His thinking holds objectivity as the basis, arguing that we often do not know what that objective truth might be, but we still must work towards understanding what holds us together as humans. This is a confirmation, when evaluated, that objectivity is essential to focus on.

In conclusion, objectivity and subjectivity are crucial to good thinking as the process pushes us to be more accurate in determining where subjectivity is valued and where objectivity should be valued. When understanding our world and its people, a thinker must be able to carefully and constructively think through problems with great diligence and respect for all involved. Thinkers acknowledge the different experiences of individuals and the experiences, factors, thinking processes, or other influences that hold us together as humans. Without the created awareness of both elements, we can not understand how unique each situation or person we will be confronted with is, or equally importantly, how each of us is connected by mutual understanding or objective factors that might not be easily apparent.

Watch Terry Fox’s story. Evaluate where the intersection of objective and subjective values is most revealing in this powerful narrative.

References

Arruda, D. (2008, March 30). Terry Fox – ESPN. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjgTlCTluPA

Galef, J. (2016, February). Why you think you’re right — even if you’re wrong. Retrieved

from https://www.ted.com/talks/julia_galef_why_you_think_you_re_right_even_if_you_re_wrong?language=en

Gardner, C. (2009, June 03). Chris Gardner UC Berkeley keynote 2009 (HQ). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=vtYpJzQkx1Y

Gilbert, D. (2005, July). Why we make bad decisions. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_gilbert_researches_happiness?

language=en

Iyengar, S. (2010, July). The art of choosing. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/sheena_iyengar_on_the_art_of_choosing

Loeb, P. R. (2010). Soul of a citizen: Living with conviction in challenging times. New York: St. Martins Griffin.